A long summer's day on a cliff called Byōbu leads to a change in perspective

2.15am, Tokusawa: shooting stars are slipping out of the sky as we leave the campsite. One runs ahead of its trail, falling into the darkness like a glowing coal. Too bad that we can't spare the time to watch; every minute counts if we're going to climb him to the top. In silence, we chase the wavering beams of our headtorches up the valley path.

3.15am, Yokoō: breakfast is a couple of rolls in front of the hut, washed down with canned coffee from a vending machine. It's good that it's still dark, because he can't play mind games with us. In daylight, his profile looming above the trees would start raising questions. As in, is this steep enough for you, punks?

For a time, Byōbu was too steep. To get up that sheer skillet, you'd need artificial climbing techniques. We didn't do aid; therefore we couldn't climb Byōbu. Then, one September weekend, the props were kicked out from under that syllogism; our president and vice-president – that was Sandra – did two routes on Byōbu. The possible had just been redefined on us. I picked up the phone; it was time for action.

3.30: We enter the side valley, then wait quarter of an hour before it's light enough to wade across the stream. It's good that the face is still in shadow: in better light that central buttress would stand aggressively forward - less like an elegant lacquered screen, as its name should imply, than some windowless and totalitarian bastille. Welcome to the Ministry of Truth.

After the stream crossing, it's a half-hour scramble up a rubble chute of pulverised stone. Under one boulder is trapped a fragment of a shattered climbing helmet. I try not to speculate how it got there.

5.30: we're at the foot of the cliff, sorting the gear, just ahead of a trio of climbers from Nagoya. They've bivvied nearby, in a nest of panda grass. That was what Allan and I did last autumn, in our first visit to Byōbu: I remember a harvest moon rising into a field of altocumulus, turning the sky into rippled silver. A bad sign, as it turned out.

5.50: Today, the weather is flawless. In the growing light, I step off a patch of frozen snow onto the rock. A series of avalanche-rounded bulges leads upward; all the handholds have been smashed or smoothed away. Then Ken leads past, tackles an awkward overhang, and finishes the second pitch tethered to a stunted silver birch.

Now we're on T4 - T stands for 'terrace', but it's more like a steep patch of trees clinging to an island on the face. With the ropes draped around our necks, we stumble up it on the trace of a path. This is just the approach: the real climbing hasn't started yet. Yet the woods of Yokoō are already far below; the river has dwindled to a thread; its roar to a distant murmur.

8am: we flake out the twin ropes for the second time so that Ken can start on the first pitch. Route finding will be easy; that corner shows the way, arrowing upwards between granite walls. The climbing is "continuous at the grade", which means, translated from guidebook-speak, that it's hard all the way up.

But Ken is making steady progress. As his brightly clad figure dwindles into the face, I start to appreciate the cliff's scale; he's going to run out almost every centimetre of our fifty-metre ropes. The searchlight glare of an August morning is now flooding the face; I feel the sun scorching the black rubber heels of my rock-shoes as I come up.

When I arrive at the belay, Ken is still ebullient from his lead: "Anywhere else, that would be a climb in itself," he says. But here it's just the first pitch. My turn now: I clip a sling into a bolt above the belay and use it to start a hand-traverse, feet slapped onto holdless granite. Then it's a matter of edging crab-wise along a sketchy ramp, body flattened into the rock. The forest below shrivels into a mere herbarium.

I pull onto a ledge floored with smooth gravel and a soft stratum of cigarette stubs. Shielded by a pinnacle, it's a good perch while we eat another roll, watch the Nagoya three clinging like human flies to the neighbouring skyline, and drink the last of our water. Might as well go light for the next pitch, a near-vertical wall of blank granite, innocent of cracks and holds. In fact, we haven't a hope of getting up it without the handywork of a previous generation of alpinists.

Some 34 years before us, a trio of young Japanese climbers - the leader was 28 - woke from a bivouac on this very ledge and set to work. They'd hauled up heavy sackfuls of ironmongery for the job - starting out with 65 pitons and 38 of the new-fangled expansion bolts. Most important, though, was their attitude; they were out to redefine the possible.

This revolution had started in January 1955, when two rival climbing teams converged on Kita-Dake Buttress in the Southern Alps, vying for the same line. When they met up under the cliff, they decided to join forces. The long winter bivouacs on the face gave them ample time to discuss the state of Japanese alpinism.

How about it, somebody asked, if they formed an elite club. Recruiting only the very best climbers from the leading clubs, they would concentrate on big wall climbs, push grades up to top European standards, and train for new routes in the Alps and Himalaya. They would be Japan's answer to the

Groupe de haute montagne, those praetorian guards of French alpinism.

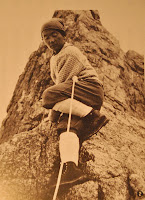

In January 1958, the new group took shape around Okuyama Akira (right), one of the Kita-dake leaders. They decided to call themselves the RCCII, harking back to the

original Rock Climbing Club of Kobe, the outfit founded in 1924 by Fujiki Kuzō to pursue technical climbing. Fujiki, who was still around, thought the RCC name was worn out, but it found support from Fukada Kyūya;

the Hyakumeizan author always had a soft spot for history.

The RCCII made its first mark in June the same year when they climbed an impossibly overhanging face in Ichinokura-sawa. Using expansion bolts for the first time in Japan, the climbers were able to cross blank areas of rock where traditional pitons couldn't be used.

Then, in April 1959, RCCII member Minami Hakuto (left) and his crew pounded a vertical row of expansion bolts into the very slab that now loomed above us. Altogether, they spent four nights on Byōbu-iwa. Borrowing the name of Minami's home climbing club, they called their line Unryō: "cloud ridge".

Over the next decade, routes like this helped to drag Japanese alpinism - I could imagine it gibbering and squeaking a bit, like myself following one of Ken's bolder leads - out of its III/IV comfort zone into the hard new world of V/VI.

RCCII faded from the scene after Okuyama's death - he took his own life in 1972 to forestall the cancer that was killing him - but not before its members had put up a first Japanese ascent of the Eiger north wall and attempted Everest's south-west face.

Minami, by the way, is still around

Minami, by the way, is still around. And so, it appears, are the very bolts that he drilled into Byōbu three decades ago. From the safety of our luncheon ledge, we are now inspecting these with misgivings; some of Minami's originals appear to have been bashed out of shape by avalanches; most have lost their rings. As makeshift replacements, more recent climbers have threaded the bolt-heads with 3mm shock cord. These so-called hero loops are frayed and faded, but we have to use them or give up the climb.

Ken clips his first étrier into one of these loops - it's his turn to lead again, thank goodness - and he steps up with care. The suspense grows as he gains height: a fall is unthinkable on this crummy protection; the whole rig might unzip. At half height, somebody has installed a modern Petzl bolt - now, at least, the lead climber won't deck out if something comes awry. More daunting still is the place where the bolts stop, forcing the leader to climb free on steep rock before reaching the belay.

At 1pm, we're both standing on a small ledge at the top of the third pitch -in the same place, last autumn, Allan and I looked out at Jōnen and saw the pyramidal peak dissolve into an advancing rain squall. It was time to bail: we reached the ground after three huge abseils at the limit of our ropes. Today, however, the clouds look puffy and innocent. We decide to carry on to the top.

This is where we part company with Minami & Co. Climbing in the spring, they continued to bolt their way straight up, through an overhang. As, in this season, we don't have avalanches to reckon with, we can free-climb - without aid - sideways into a gully, and thence upwards.

That traverse, though . My feet are on a bulge that slopes outward into space. To make the move, I pull outward on this rock flake, an elephant's ear of crumbly granodiorite. As I put my weight on it, the stone emits a creak. The adrenalin charge hits like an electric shock and propels me, skittering on tip-toe, across that plunging slab. It's only when we get into the gully that we realise how cool it's become; the sun is long gone behind the cliff.

The topo doesn't even dignify the gully with a route description - it just indicates the direction to follow with an upward arrow. Yet there are still three or four pitches to climb. Ken is in the lead again when we come up against a huge clod of earth and matted tree-roots blocking the gully. To evade this relic of last winter's avalanches, he goes out on the gully's side-wall and clambers, no holds barred, through a couple of trees.

4pm has ticked by when we scramble up the last grassy slabs into a low wood. We unrig our last belay, to a pine tree, and stuff the ropes into our sacks. The Nagoya trio have topped out; we hear their voices above. Now what? Ken finds the escape route, up an earthy rake through the trees.

This takes us, unexpectedly, to the brink of another chasm. Twin gullies, gnawing from either side, have almost severed our cliff from its parent mountain, leaving just a sliver of ground between them. Seemingly, the two sides are joined only by a tangle of creeping pine roots. Stepping onto this knife-edge bridge of dreams, we understand. Byōbu really is a screen; free-standing, frail, hardly less temporary than ourselves.

References

Yama to Keikoku magazine, July 1993, Classic routes of Japan series no 4, Byōbu-iwa, East Face, Unryō Route. (屏風岩東壁 雲稜ルート

Yama to Keikoku illustrated history of Japanese mountaineering (目で見る日本登山史 by 川崎吉光、山と渓谷社)

Web article about the history of RCCII:

第二次RCCの活動と歴史 by 松浦 剛

The YamaKei guidebook (see References) that quotes these statistics also draws attention to some curiously striped terrain on high mountaintops. It is wind erosion, says the article, that is responsible for these alternating strips of grass and gravel. You can see them at Kisokoma-ga-take (photo below) and Shirouma, among other places.

The YamaKei guidebook (see References) that quotes these statistics also draws attention to some curiously striped terrain on high mountaintops. It is wind erosion, says the article, that is responsible for these alternating strips of grass and gravel. You can see them at Kisokoma-ga-take (photo below) and Shirouma, among other places.

Whether or not this explanation holds – maybe somebody should go and take another look – nobody would deny that Japanese mountain winds can shift the real estate. Bashō himself testifies to that:-

Whether or not this explanation holds – maybe somebody should go and take another look – nobody would deny that Japanese mountain winds can shift the real estate. Bashō himself testifies to that:-

According to the YamaKei authors, the driving force behind Japan’s strong surface winds is the jet stream. Or rather two of them. In winter, the Himalaya often splits the polar jet into northerly and southerly streams – which then flow back together just to the west of Japan, causing atmospheric mayhem.

According to the YamaKei authors, the driving force behind Japan’s strong surface winds is the jet stream. Or rather two of them. In winter, the Himalaya often splits the polar jet into northerly and southerly streams – which then flow back together just to the west of Japan, causing atmospheric mayhem.